Once We Were Slaves, But Now We Are Free

As a child, slavery seemed like a foreign concept. Then I realized my grandfather had been one.

My grandfather is *not* in this photo. This image was shared by a family member, whose father is pictured along with other conscripted slaves.

Toronto, 1986. Passover

Zaide tends to race through the Seder. He speeds through the entire Haggadah so quickly that the words bleed together, turning it from a story into a mantra. His old-world Ashkenazi pronunciation of the words sound misplaced. It’s not the kind of Hebrew they speak in school. There are s-sounds where there should be t’s. Add to that his thick Hungarian accent, made all the more gravelly from decades of heavy smoking. This is not meant to be fun, I register, as Zaide dips his finger into the wine and splashes it on the special Pesach china like blood to commemorate each plague.

He looks up at Ica, his wife and continues the story as if the entire Haggadah is imprinted on his brain. Bubbe Ica gives him a nod to continue speeding along. The food is ready and she’s anxious to serve it. Mom is also impatient, her book closed on her plate. She acts like a visitor, as if the entire ceremony is foreign to her. Dad stares at his watch, taking a potato and dunking it in salt water ahead of its turn.

Zaide raises his voice and breaks into a melody, if not an outright song, to get everyone to focus. Avadim hayinu, he recites more loudly. We were slaves to Pharoah in Egypt. We don’t get to the freedom part until later. For now, we sit in our discomfort channelling the idea that we were all once prisoners, victims of an oppressive power.

I try to embrace it. Slavery. But it is the stuff of films and ancient history. Only years later, will it mean something new, as I learned about modern day examples and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.

But it was only years after my grandfather’s death that I realized he, too, had been a slave. He never spoke about it. Not a word. In my grandmother’s broken English I understood that he was “taken” to a “work camp” somewhere in “Russia.” It sounded mysterious, almost innocuous. The truth was much more terrifying.

The Hungarian Labor Service was created early in the war as a means to utilize undesirables, such as Jews and communists, who were considered unfit to carry arms and as a result, not useful to the regular military. They were expendable human capital, ordered to clear minefields or sent to the war front, without weapons, without a second thought.

My grandfather, Herman Kohn, was one of the almost 100,000 Jewish Hungarian men forced into the labor service. He was “taken” sometime at the end of 1942 or early in January 1943. According to reports, many froze to death that winter, wearing only the clothes they left with.

Finding information about my grandfather, Herman Kohn, has been a painstaking task. Over 80 percent of these men never returned. Many of those who did, like my grandfather, never spoke about it. I am still trying to put together the pieces of my grandparents lives early in the war, but the picture is coming into focus. Here’s a start:

Ilona Weisz and Herman Kohn married on August 25, 1942 in Nyíregyháza, in Hungary. She was 25 and he was 32 — a little old for Orthodox Jews.

Herman loved Ilona, whom everyone called Ica, (or Kitty.) He asked her to marry him several times. Ica said she initially rebuffed him because he wasn’t her type. He smoked too much. Drank. Gambled.

Ica was previously engaged to someone else, a Jozsef Grunstein from Mukachevo, which is now in Ukraine, but was then part of Czechoslovakia. In 1938, news of Ica and Jozsef’s engagement was published in a local newspaper. Ica would have been 21 then — the perfect marrying age. Why did she change her mind and wait four years only to marry a man she knew since childhood? Meanwhile, there was a war raging around them, with men Herman’s age already “taken” and rumours of death camps outside of Hungary’s borders.

There are family anecdotes but nothing concrete. Not yet.

I imagine Herman and Ica likely married in the new synagogue in Nyíregyháza that was completed only ten years earlier in 1932. I stood in its foyer only a few months ago, and wondered if they too stood there in another lifetime under a chupah. I explored the mikvah underneath, that Ica and possibly Herman, would have immersed themselves in before their wedding night. I have a photo of the happy couple from their wedding day. No other pictures survived.

Herman and Ica’s last known address during the war was at 20 Mák Utca (street), just one kilometre away from the synagogue. A pink house still stands there. A couple years ago, I tried to convince the current residents to let me visit but they refused.

I can’t help but imagine that Ica and Herman were happy together for a moment, playing house as newlyweds in their single story home overlooking a park. But less than six months later, in January 1943, Herman was gone, a conscripted labourer, a slave, now missing in action somewhere on the Soviet front.

There would be no further signs of life from him for the next four years.

There wasn’t a once-size-fits-all forced labour experience, explains Dr. Robert Rozett, formerly the Director at the Libraries at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem and the author of “Conscripted Slaves: Hungarian Jewish Forced Laborers on the Eastern Front During the Second World War.”

While there were about 100,000 Jewish forced laborers, close to half, about 45,000 Jewish men (and about 1,000 non-Jewish men) were sent to the Eastern Front, where the Hungarian army was an occupational force, to hold part of what was then the Stalingrad line.

The other half stayed in Hungary. Some several thousands of the ones in Hungary were brought into Austria in the fall of 1944 to build fortifications. Some ended up in concentration camps (it was in the Mauthausen area) or were massacred. Still, some who stayed in Hungary managed to leave their units and find refuge. Escape. They were the lucky ones.

Like Herman, Dr. Rozett’s father was a “conscripted slave.” They were both among the labourers sent to the Eastern front. After some digging, Dr. Rozett found my grandfather’s name in a Yad Vashem database, created from index cards recovered from the Hungarian army. Herman served in the 108/72 TMSZ company. Dr. Rozett gave me an Excel spreadsheet of other men discovered in the same company but I’ve yet to find information on any of them.

Herman was among many who disappeared in January 1943 on the Eastern Front, in the wake of the Hungarian defeat at Voronezh on January 13, 1943. Some in his company were listed as missing in Ozerki on January 25. According to Dr. Rozett, there was a Kolkhoz (collective farm) between Stary Oskol and Novy Oskol, which the Soviet forces would have reached after they breached the lines at Voronezh.

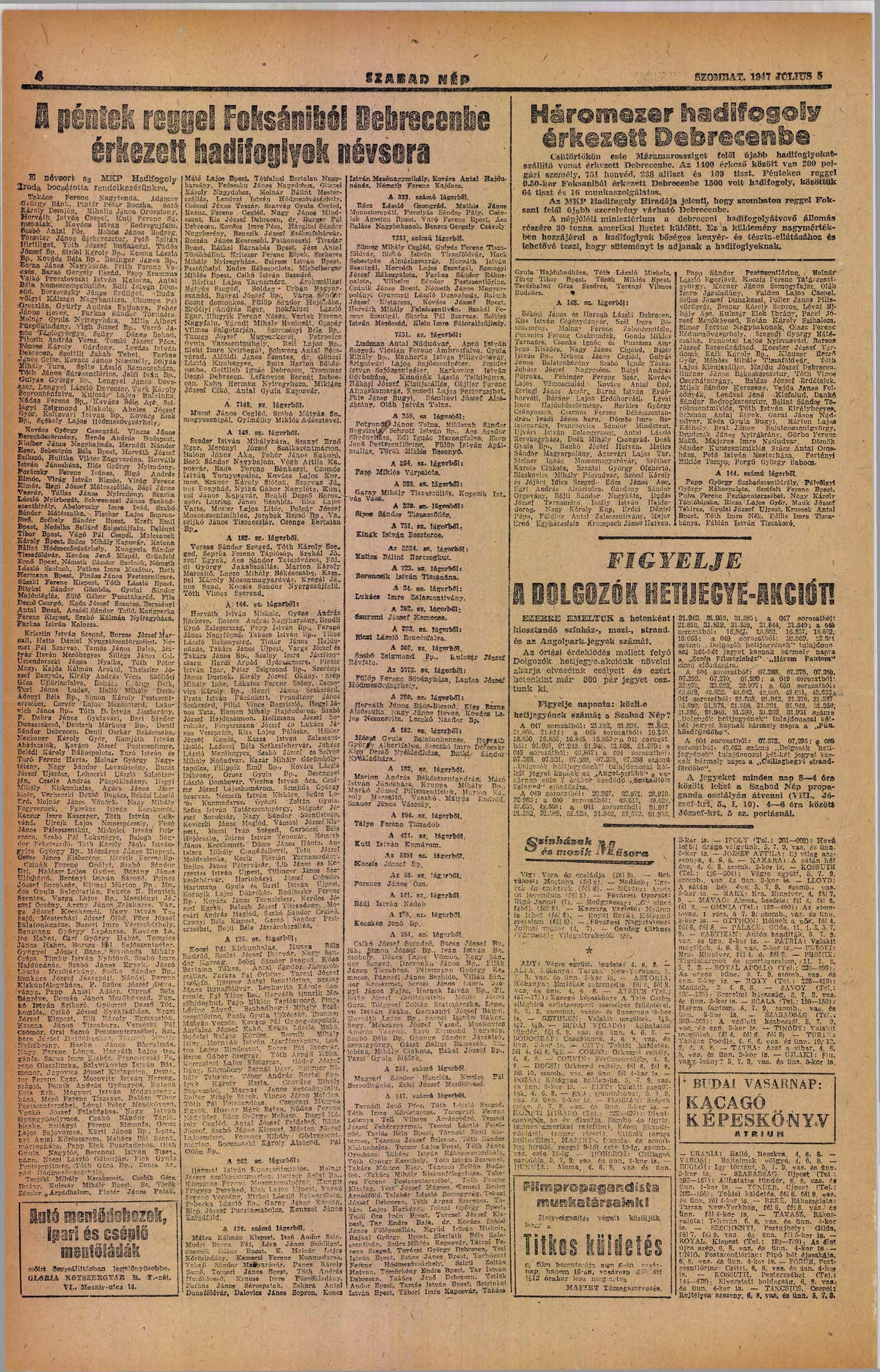

Herman wasn’t heard from again until June 5, 1947. A notice in a paper announced his return with a handful of other prisoners of war. He was held in quarantine for 10 days before being sent home. Ten months later my mother was born.

Newspaper clipping where my grandfather’s name is listed as a returning POW.

What happened to Herman those four year when he was a prisoner? I’m still searching. Dr. Rozett said that if he was taken as a POW, the Soviets would have interviewed him, at least twice, but those records are not accessible. So I keep looking.

Dr. Rozett understands my need to know. He encouraged me to keep digging, explaining that he had written the book not because it would “sell a million copies,” but rather, it would provide some insight to those of us still connected to slavery, who can never know enough.

"I wrote this book for people like you," he tells me. His words hit me harder than they should. Like him, I’m writing this book, The Synagogue and the End of the World, for people I haven’t met yet. But one day, I expect a call. And I can’t wait to answer.

Other Stories in This Series:

Searching for breadcrumbs

Forty years later, I can’t shake the feeling that I’m still searching for breadcrumbs.

I tell myself to trust the process: that I possess the insight to spot the breadcrumbs that will lead me to the answers to my story. I must believe that I can find the trail and put it all together.

“Should ve check for crumbs?”

"You are Like the Dew"

For the last 25 years, I’ve taken these tapes with me everywhere. Every time I move, they are with me, on my body or in my purse. I don’t trust them to a box. When I run the mental gymnastics of what I would save in my home case of a fire, I don’t think of photo albums, or the kids’ yellowing art work. I think only of the tapes.

The cycles of cruelty are never ending, sometimes ameliorated sometimes returning in full force. Humankind is simply not kind, alas. Outsides become insiders only to be turned out again. May your writing be a light to a different way, inspiring at least one or two!