My uncle was all memory, my mother all forgetting

They were two sides of the same coin. For years, I held my mom's self-imposed amnesia against her not realizing that my uncle's dedication to memory likely hastened his death

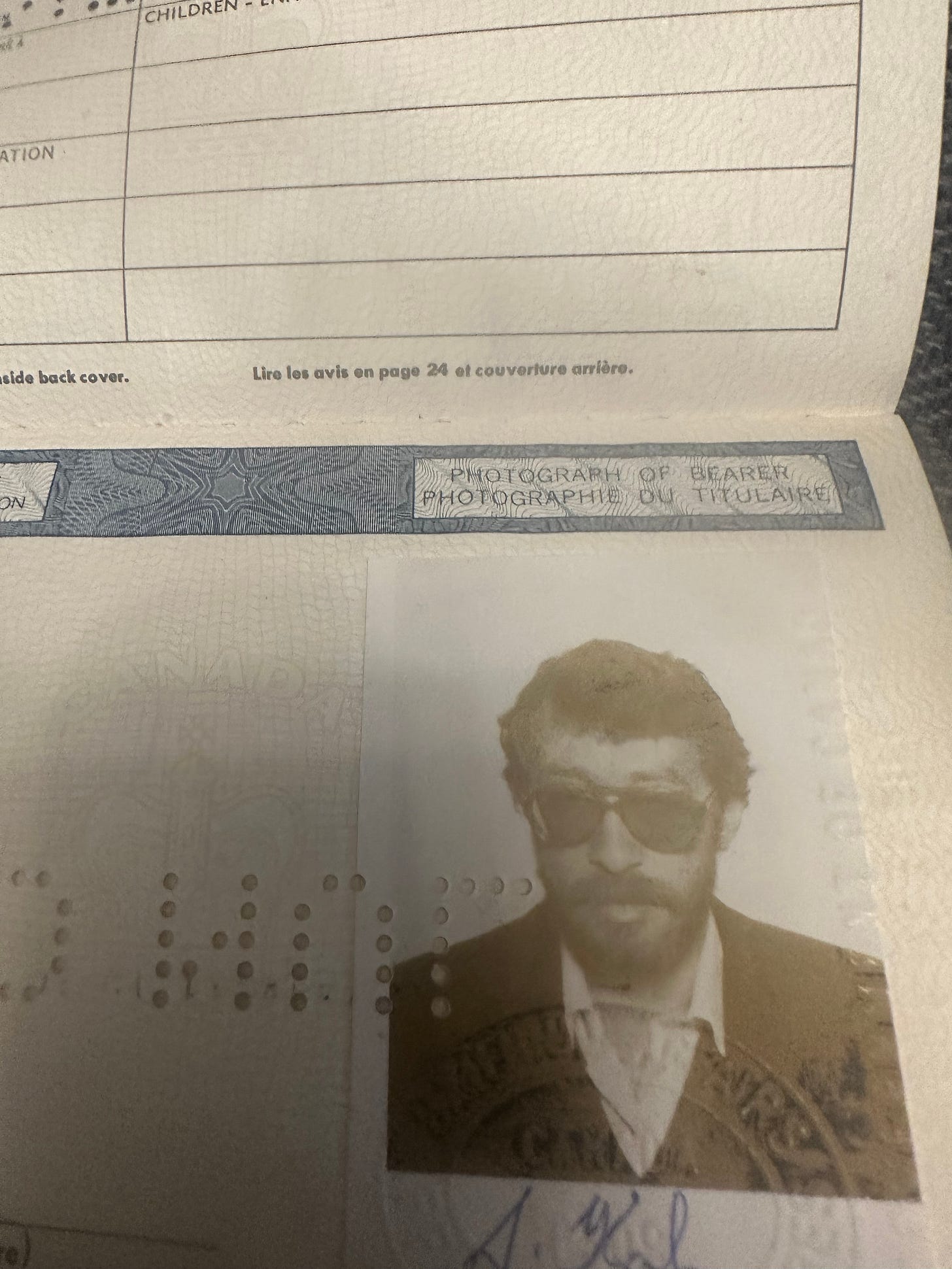

A photo from my uncle Andrew’s expired passport — one of the few artifacts he left behind. Doesn’t he look like a gangster?

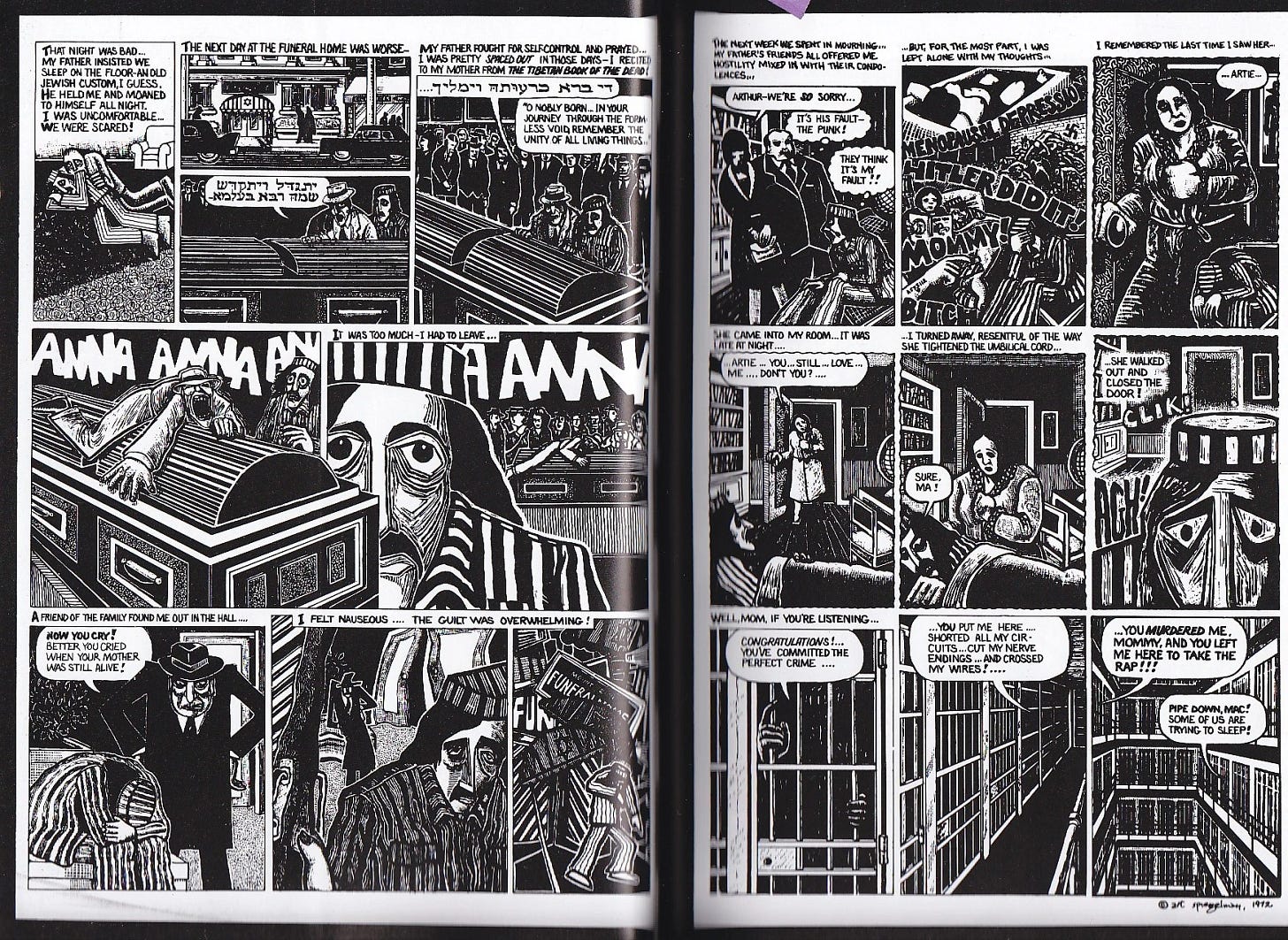

I was at university when I first discovered Maus. At the time, getting my family to talk about the Holocaust was harder than pulling teeth but Art Spiegelman did something miraculous for me. He laid all my family trauma out on an operating table, allowing me to look at different pieces bit by bit. I was never the same.

The beating heart of the graphic novel, the meta comic-in-a-comic called Prisoner on the Hell Planet, is where Spiegelman really exposes the core of the wound. And immediately, after seeing Artie in the striped prisoner outfit his psyche always wears, I saw something familiar, something I hadn’t really noticed before.

I saw my uncle, Andrew.

Admittedly, as a child I was sure I could see things others didn’t: kippahs on bare heads of people I knew to be Jewish, ghosts at a funeral and the striped prisoner outfits on people trapped in history. My uncle Andrew was one of the trapped.

In September, it will be 17 years since Andrew suddenly died. I say suddenly since none of us knew he was sick, at least not with Leukaemia. It was understood that he was a “drinker” (read: addict), told tall tales (read: delusional), suffered mood swings and often disappeared (read: undiagnosed mental health issues) but Leukaemia took everyone by surprise.

I was at work when I got the frantic call from my mother that Andrew — her brother— had been admitted as a John Doe at one of the hospitals downtown. I didn’t say a word to anyone at work. I just started walking to the hospital.

I remember my heels — I had invested in several pairs of fancy shoes for my job as managing editor of the digital newsroom at Reuters. That day I wore the Louboutins; they were the most comfortable and that’s not saying a lot. Until that day, I kept them pristine, never wearing them outside, but that day I walked the 10 blocks, imagining their precious red bottoms scratching on the pavement with every step. The shoes were me playing dress-up. I was still the kid my uncle had whistled at when he wanted my attention. When I’d yell back that “I wasn’t a dog,” he’d reply. “But you came when I called you.”

I was the kid who found him drunk with friends in the synagogue basement on holidays. I was the kid who begged my grandmother to kick him out until he learned to stop yelling at her. I was the kid he spoke to about history, literature and God, and when he loved me, he made me feel like I was too good for anyone, even for this world. The heels were just a costume I put on, for my alter ego as a journalist.

My uncle was in a coma by the time I arrived. My mom and dad were already there, but not long after my arrival they took the opportunity to leave. Andrew often made people uncomfortable and his imminent death only appeared to exacerbate that issue.

You see, for years, my uncle was our family’s memory, while my mother was its forgetting. They were in every way opposites, two sides of the same coin. He was Orthodox, she feigned near-ignorance of the faith that she grew up in. He told family stories, she pretended not to remember. They agreed on nothing, not even the number of years between their ages. (It was six.)

Even as a child, I understood my mother’s will to forget as a defence mechanism. What I didn’t see coming is how my uncle’s obsession to remember led indirectly to his death.

Back at the hospital’s emergency ward, I kicked off my Louboutins and lay beside him. He was only 53 but I didn’t know that back then. I could never ask him his age. In that hospital bed I noticed, maybe for the first time, how beautiful he was — something my grandmother always said, but in the last few years before he died was hard to notice. He often smelled of stale smoke or weed, his clothes ragged. No one knew where he slept most nights but I suspected people’s sofas, or the streets.

I tried not to think of my grandmother in that moment. His only real home was my grandmother’s sofa. She would be there now, waiting for news, knowing that this would be the last time he disappeared. (I write about him disappearing HERE.)

“Can he hear me?” I asked the nurse.

“I believe he can,” she replied.

So I sat there, and talked to him. I touched his hair. I touched his face. When my uncle was good, he would touch my cheeks with such love, as if checking to make sure I was real, telling me without words that I was the daughter he would never have.

When he was good he was so good, insightful, creative, funny. The only other reader in the family besides me, who spent most of his life in yeshivas yet seemed to know everything. I always called him my favourite uncle. It was slightly ironic. Our family is very small. I don’t have many.

“He has a very aggressive form of Leukaemia,” the nurse said. “It looks like he refused treatment. His doctor has been trying to reach him for weeks.”

I nodded. A week earlier, Andrew had asked to meet me for dinner and I declined, having already made plans. “Maybe next week,” I said. But of course, there would no next week. He must have known that but decided against saying anything.

He died that day in the hospital, in many ways taking all the memories with him.

After he died, I remember going through his belongings, a solitary backpack I found in my grandmother’s apartment. It was filled with a large freezer bag of weed. Too big, I thought, for personal consumption. Likely he was selling parts of it. I made the mistake of staring at it for too long, so my dad noticed and asked me what it was. I didn’t think fast enough to say “oregano,” so he confiscated it. The backpack held dozens of liquor store receipts, for the same bottle of whiskey again and again, sometimes one, other times two. Then there were pieces of paper torn from electrical poles advertising classes in Word processing and basic computer skills. Somewhere deep inside him he wanted to improve. I know he wanted to.

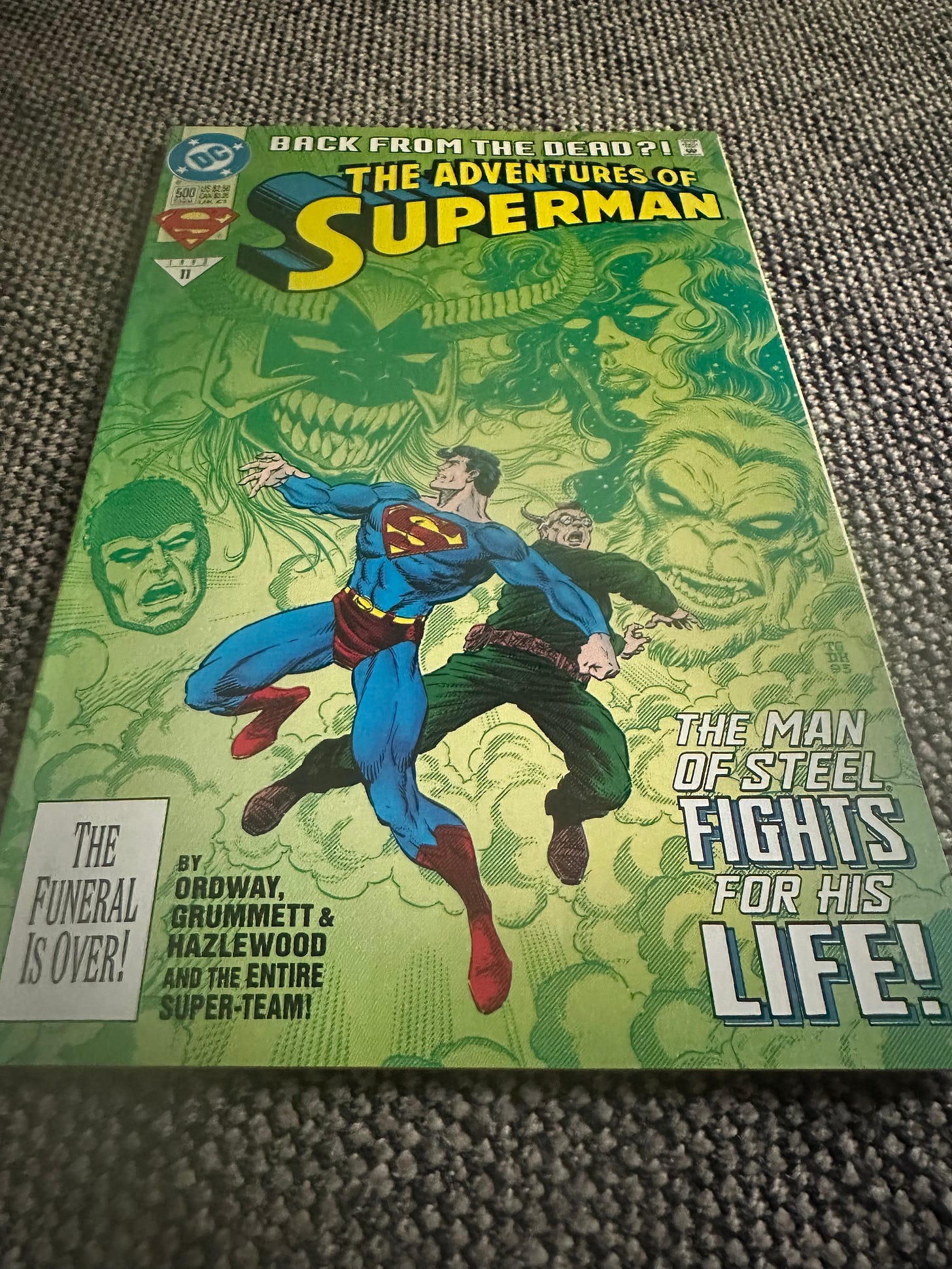

Except these weren’t his only belongings. My grandmother handed me a box he kept in her closet. In it were a dozen old comic books, each neatly tucked into its own individual sleeve.

I’ve been thinking about those comics, ever since I wrote about Magneto and the Use and Abuse of Holocaust Memory .

My uncle loved comics, often donning inappropriate cartoon images on t-shirts that I remembered from the shuk in Jerusalem. His love extended to anything sci-fi, like Star Trek (I always looked away when Spock gave his Vulcan salute, just like I did in synagogue when my uncle and grandfather did the same on the bimah). I thought Andrew’s love of comics to be quirky, maybe even juvenile, but in the ensuing years, I, too, have become enamoured with the Jewish backstory of many superheroes and villains. It has made me view my uncle’s collection with a different lens.

Superheroes draw their strength from pain. Historically, so do Jews. My uncle struggled, really struggled, with the experiences of his parents, my grandparents. He looked for strength, for good and bad, for things to make sense when then rarely did.

One of his Superman comics, from 1993, has Jonathan Kent (Clark Kent’s father) in a coma, chasing Clark (Kal-El) into the next world. (Kal-El has been translated by some to mean voice of God in Hebrew.) In his near-deathlike state, Jonathan finds himself back in the Korean War, his memories of the past mixing with the present. Somehow, Jonathan pulls through. He finds his son, a God-like man, and returns to the living. An incredible feat for a mere mortal but also a testament to the power of love and pain, and memory.

I don’t know where my uncle went during those last moments in his coma. I don’t know if he really heard my voice and if it helped him find his way to whatever it was he was looking for. But all these years later, I can still hear him sometimes. He can be angry or sullen but sometimes he whistles and I answer the call.

“I’m not a dog,” I tell him in my mind.

“Maybe not,” he smiles mischievously. “But then, why did you come when I called?”

This piece is both poignant & thought provoking. It makes me think about the roles people play in families. Perhaps your role, as a writer, will help synthesize the forgetting & the remembering in a healthy way.

Even from this short excerpt, I feel like I know your uncle well. And I relate to him. You’ve brought him to life on the page.

🙏🏻❤️🙏🏻

Thank you for writing your story about Your uncle. It was very well written and full of compassion.